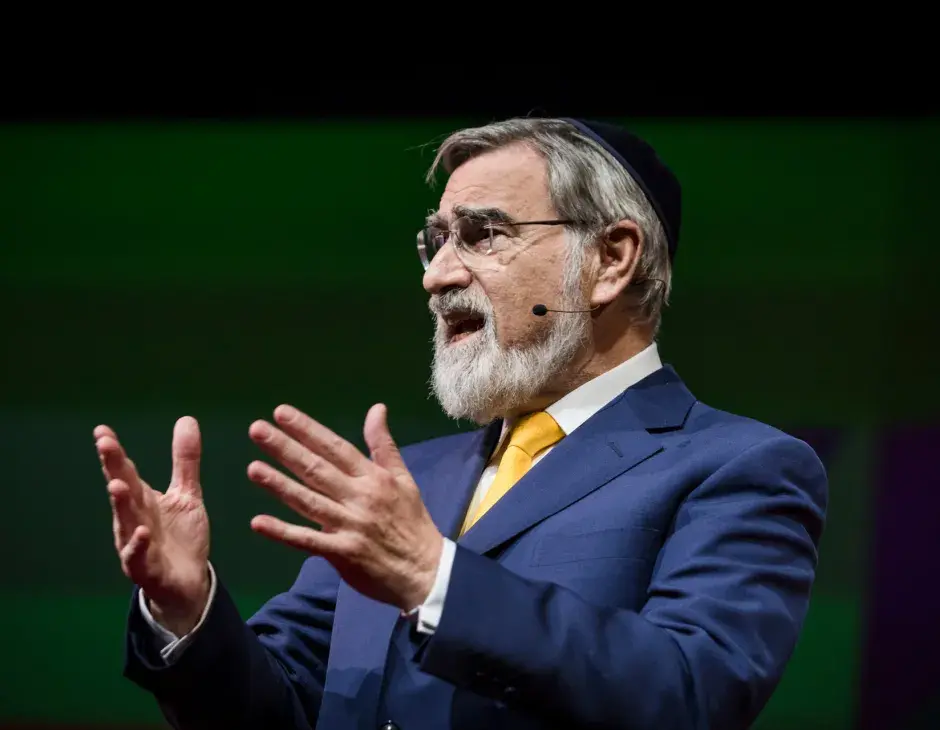

Rabbi Alex Goldberg is Dean of Religious Life and Belief at the University of Surrey and a 2015 KAICIID Fellow. He was a mentoree and student of Rabbi Lord Sacks.

Chief Rabbi Lord Sacks was my mentor and my teacher. He encouraged me into the rabbinate and his signature is on my ordination certificate.

Perhaps no other religious figure in my lifetime has so influenced public discourse within Britain in the way he has done in the last 40 years. Rabbi Sacks was a writer, a thinker, a broadcaster and leader of the Orthodox Jewish community in the British Commonwealth and beyond. Indeed when Britain withdrew from Hong Kong in 1997, the local community asked him to remain as their Chief Rabbi. His writings were translated into public policy in the UK and no more so than in the question of how best to integrate and bring together individuals and communities from diverse religious and ethnic backgrounds.

Born in South London in 1948, Jonathan Sacks was educated at Gonville and Caius College, University of Cambridge where he gained a first-class honours degree in Philosophy. He often describes how he had an awakening as a result of the Six Days War in 1967 and travelled to America to meet a number of rabbis: in doing so, he encountered the Lubavitcher Rebbe Menachem Schneerson, who remained an influence on him throughout his life. It was the Rebbe who convinced him to enter the rabbinate. Sacks managed to straddle academia and the rabbinic world throughout his career, obtaining both rabbinic ordination and his doctorate in London. He would spend his career seamlessly at times bridging the worlds of the rabbinate, academia and public discourse.

It was in his role as Chief Rabbi of the British Commonwealth that he came to the fore in Britain and became widely known to millions through both his writings and his frequent broadcasts to millions on the BBC’s Thought for the Day. He was an advocate of better community relations: his views on this are laid out in a number of books that include Dignity of Difference, The Home We Build Together and Not In God’s Name. His works laid out a worldview and philosophy that saw room for diversity and difference: in theological terms he believed that G-d had both particularist and universal covenants (and blessings) with different groups and with humanity as a whole. For him, society was under threat from both excessive individualism and possible totalitarianism: he saw a free society where communities cooperated with each other within the sphere of civil society as checks to both these excesses.

His ideas reset the notions of how interfaith and intercultural work could be done in the UK, ideas that were adopted as public policy by the Government. Sacks best explains this idea when describing how different faiths can best bring about peace: “There are two different ways. One is face to face, by doing dialogue, sharing our respective beliefs, but it’s a long, slow process, undertaken by rare and special people, and can easily be undone. The other is what I call side by side, which happens when people of different faiths, instead of talking together, do social action together, recognising that whatever our faith we still need food, shelter, safety and security. Our basic humanity precedes our religious differences”.

For me, personally, I shall remember him as my teacher. We did at times debate. He would encourage it even when I thought I had no more to say. I recall having dinner with him at the University of Surrey when I was working for the Government on community relations. He asked me about the theory behind the work I did in intervening in communities experiencing heightened levels of tension and how we promoted community cohesion and integration. I spent the next five minutes laying out both the academic thinking and practical realities around the work we were doing on the ground. When I finished, he paused to lay back in his chair: “Very good” he said “Now expand on this”. It is this challenge that led me to my relationship with KAICIID.

I shall miss our discussions and exchanges: which in the main were on philosophical and social issues: the rabbi in the public sphere. As he said to me ‘I wrote the books so all could learn’. He leaves behind over 20 books, countless hours of broadcasts and talks. So whilst he has gone and there is gaping hole where he once stood, he has still so much more to teach me.