Protecting Cultural and Religious Heritage: The Battle of Unknown Soldiers

Historical and archaeological sites, along with ancient sculptures, monuments and manuscripts stand as a testimony to our diversity and complex history. They are also the edifices of our forefathers’ achievements. Throughout history, invaders and extremists attempted to demolish them with the aim to annihilate nations’ collective memory and impose their rules. Examples from around the globe include recent incidents. In 2001, an extremist group in Afghanistan demolished two ancient Bamiyan Buddhas sculptures. In 2015, the so-called Islamic State destroyed archaeological sites in Palmyra, Syria.

In light of rising attacks on religious and historical sites and the increasing violence in the name of religion, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution in 2021 to protect religious sites, with the aim of safeguarding tolerance as well. The resolution, proposed by Saudi Arabia on behalf of eleven Arab states and nine other countries, stated that “religious sites are representative of the history, social fabric and traditions of people in every country and community all over the planet and must be fully respected as places of peace and harmony where worshippers feel safe to practice their rituals.”

Through its Dialogue 360 project, KAICIID has supported several initiatives in the Arab region to protect heritage and historical sites. In these initiatives, sites have been used to promote interreligious dialogue, coexistence and tolerance by retrieving memories of times when diversity was respected and tolerated.

In Egypt, the Ibrahimia Media Center (IMC) launched the ‘Alexandria Peace Sites’ initiative to raise awareness of the archaeological and historical sites in the city. The project aims to rebuild harmonious coexistence between different religious groups in Alexandria.

The project included six youth coexistence workshops, six peace sites trips involving Muslim and Christian participants as well as non-Egyptian participants, and hosted a seminar about coexistence, called ‘Alexandria, a Witness on Peace’.

Coordinator Sameh Megalaa explains that the project works on promoting archaeological sites from times of exemplary coexistence to remind people of the culture of acceptance that existed in their city. “Now there is a populist culture that believes in rejecting sites built by other cultures or religious groups”, he says. However, in the past, “everyone acculturated, as one can find a mosque built in the vicinity of three different churches belonging to the Anglican, the Coptic and Armenian churches. This proves the ancient culture of coexistence that was pervasive.”

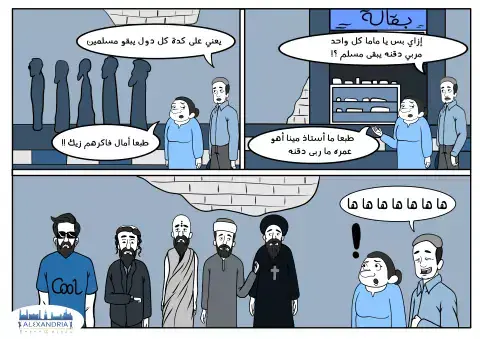

The initiatives utilised social media platforms to disseminate visuals encouraging a culture of tolerance and ridiculing segregation. Social media was also a channel to share historical backgrounds on the archaeological sites.

Sameh says religious leaders were key partners in the project’s success, especially as some of them granted them unconditional access to these sites and provided historical facts.

Raising awareness among Tunisian children

In Tunisia, a similar effort with the aim of raising awareness on diversity has been ongoing since the revolution in December 2010. Amid the political turmoil, civil society organisations have carried the heavy load of promoting interreligious dialogue, coexistence, and tolerance. Several minority groups live in the country, and although they are fully protected by law, full social coexistence still seems far away. The complex regional political developments have also cast a shadow on the effort to value all minority groups.

Tunisia has one of the oldest synagogues in North Africa called El-Ghriba on the Djerba island, which receives visits from Jews from around the world. Other minority groups include Christians, Ibadis and Bahais.

With the country’s complex dynamic in mind, the Tunisian Association for the Support of Minorities, in cooperation with KAICIID launched its project ‘Youth Educate Youth (YEY)’ to engage youth in raising awareness of the importance of protecting cultural heritage and safeguarding religious sites in the regions of Djerba and Carthage. The organisation produced two short documentaries about the religious sites in the country focusing on the historical sites belonging to Jews, Christians and Ibadis in Djerba and Carthage.

The project coordinator Rawdha Seibi believes that “stirring a conversation about the historical presence of all the minorities in Tunisia using archaeological sites as evidence, helps people become more welcoming to minorities”. Rawdha stresses that “the Jewish and Christian communities were present in Tunisia for centuries and are native to the country”. However, not many people in Tunisia are aware of this fact.

The organisation mainly targets school children, as Rawdha sees them as “the real engine for change”. She highlights that “protecting the sites does not always mean protection from demolishing, but it also includes preventing the authorities from turning these sites into venues for other activities.”

Speaking on the role of religious leaders, Rawdha says that the project has worked closely with Christian, Jewish and Muslim leaders including the Mufti of Tunisia who helped providing historical knowledge.

Rawdha says that it is a long way to reach a genuine culture of acceptance and tolerance. “The reaction on social media regarding the documentaries is still fluctuating between supporting the initiative and criticising it,” she says. For her, “imposing a law that criminalises hate speech is easy in a country like Tunisia, however changing the minds and social norms of people is a real challenge”.

Algerian diversity on social media

In Algeria, where different ethnic groups also live, Aicha Wided Sengouga launched her project “Mirathe” [Eng: Heritage] to tell stories of historical and religious sites in Algeria. She uses social media platforms to disseminate photos and graphics that she produces with information on the site to remind people of how diverse Algeria is.

The project published seven illustrations featuring cathedrals and mosques. Mirathe also published two videos and collaborated with Tourathy [Eng: my heritage] magazine.

“Young people, including myself, were not raised to know Algeria as a diverse country with different ethnic and religious groups,” project coordinator Sengouga says. Therefore, she wanted to promote diversity using arts, photography, and narrations.

“Preserving historical and religious sites should be as important as protecting human life,” Sengouga argues. She explains that protecting these sites is an act of protecting people’s collective memory.

Sengouga faced different challenges including finding reliable sources for information on the sites. She also faced logistical challenges including reaching these locations, as they are situated in hard-to-reach areas.

Sengouga receives encouraging comments on Facebook, mainly from youth who are learning about diversity and from minorities who feel heard and seen through her project. One user wrote: “God bless you for introducing the Christian culture in Annaba,” adding that ignorance about the Christian culture was widespread.

KAICIID also supported other initiatives including another one in Algeria titled ‘Maqamat al-Salam’ which was launched in cooperation with the Mediterranean Foundation for Sustainable Development ‘Djanat Al Arif’. The initiative supported governmental efforts to preserve heritage and cultural and religious sites such as mosques of various sects, churches, synagogues, and shrines. The initiative worked on building a database of these locations along with a mobile application for easy access to the information on the sites.

In every battle for preserving heritage for forthcoming generations there are unknown soldiers. Had it not been for the few brave Malian activists, the world would not have seen the historical Islamic manuscripts from Timbuktu, the city of 333 saints.

Hosted by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in Riyadh from…