Having spent his early childhood idolising Albert Einstein before going on to study metaphysics, chemical engineering and process engineering at university, Swami Chidakashananda grew up convinced that science could end all human suffering. But after years of scouring scientific avenues for answers to the human condition, and finding none, he turned his mind instead to the spirituality of Vedanta, one of six schools of Hindu philosophy.

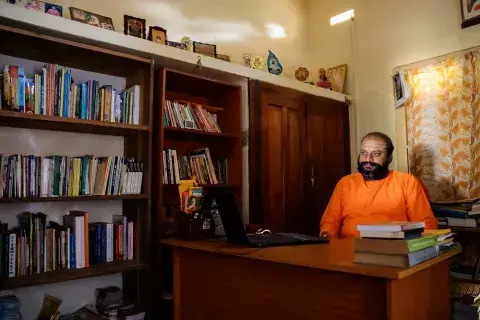

Today, Swami is a Hindu monk and one of the foremost spiritual teachers at Chinmaya mission in Jana, northern Sri Lanka.

It was at an interreligious training event in Colombo that he learned about the Fellows Programme and immediately applied to join. Since then, he has been working with other Fellows alumni based in Sri Lanka in order to coordinate local activities.

Swami says that he and his colleagues are concerned with the growing risks for young people, such as online hate speech. “There is a well-known Buddhist monk, for example, who is making speeches that denounce other minorities, whether Hindus, Christians, or Muslims. He recently made a statement suggesting that, after the upcoming elections, a monoreligious government should be formed,” Swami said.

Having witnessed the damage caused to some communities by exposure to online vitriol, the Sri Lankan Fellows designed a one-day workshop that took place in the first quarter of 2020, for which KAICIID contributed guidelines and content that was used to create instructions for recognising and reducing online hate speech, targeting people from across the island nation.

The need for such an initiative was vital as tensions were high from inflammatory rhetoric spread by senior religious leaders against people of different faiths. A number of Hindu holy sites were also desecrated, prompting followers of Sri Lanka’s minority religions — Christians, Hindus and Muslims — to urgently seek peaceful means for de-escalating conflict. In addition to his anti-hate-speech project with other Fellows alumni, Swami is working with religious leaders in Jana to provide interreligious dialogue training that also teaches conflict prevention and reconciliation. While the topics are new to the Buddhist monks and Christian priests taught by Swami, he is determined to enhance the flagging reputation, and limited understanding of interreligious dialogue in his part of Sri Lanka.

Swami believes that cynicism about the true value of interreligious work comes from the paucity of real reconciliatory outcomes within the community. “Sri Lanka’s diverse religious groups often fear that working together means that their identities are at stake. Additionally, many perceive that other religions are tied to certain political viewpoints,” he said.

Swami credits the Fellows experience with creating a marked change in his own behaviour and thought pattern. Now, when others spout hateful rhetoric about another religious or ethnic group, Swami calls to mind the principles of dialogue before reacting or giving a response.

Explaining the change in his approach, Swami reveals: “Now, when some untruth is spoken by some religious leaders or by others, the way in which I take that message and how I try to convert that argument into a dialogue, or how I deal with that situation, is all helped by the KAICIID training.”

Whereas the scope of his interactions led Swami to an insular view of religion, the Fellows Programme has given him the opportunity to interact with religious leaders from around the world and forge real friendships with “the Other”. The contact and camaraderie allow him to take a universal outlook on problems, and see beyond his immediate community to understand impacts, and seek solutions.

Now, Swami is working on a 30-year plan that constitutes his bright vision for the nation’s future. Starting in Jana, he is focusing on youth, approaching his mission not only as a religious leader but also as a social worker and community healer. Starting in 2020, he is mapping out three consecutive 10-year milestones up until 2050, for a nationwide scheme that will allow Sri Lanka’s youth to learn and live the experience of interreligious dialogue.

Through this training, Swami aims to tackle the crucial questions that lie at the intersection of one particular identity with another. For instance, does building a Buddhist temple mean that its site now belongs to Buddhism? Whose burial rituals should be followed when a religious leader dies and what factors should be allowed to influence that decision? These questions strike at the very core of the interreligious healing for which Swami sees such a great need in Jana. And only through a long-term view and panoramic lens of dialogue can the answers be universally understood and accepted.

“I have a clear vision in mind,” Swami said. “And this year, I will take that vision, plan it, modify it and convert it into a mission.”