Education is under threat in much of rural Nigeria as many children have been displaced by violence and hardship, with some schools closing due to kidnapping and violence.

Already exacerbated by the Boko Haram insurgency as well as deadly attacks and kidnappings by herders and bandits, some targeting schools, educational opportunities for children in rural Nigeria continue to suffer due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

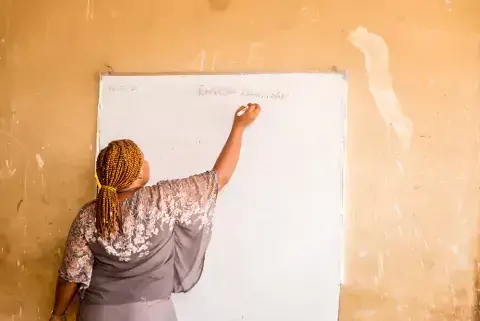

At the Pigba IDP Camp Nursery and Primary school, pupils chorus their enthusiasm, aften genuflecting with the words: “Good morning sir. We are happy to see you. God bless you.” This form of greeting, common in urban schools, was adopted by pupils when they began attending the school after it was established in October 2020.

The IDP camp is located on an abandoned estate in Abuja Capital Territory, and was settled more than five years ago by internally displaced persons as they arrived in Abuja. The camp hosts more than 2000 people, many of whom are children.

Read more about the camp and see it here.

Following a visit in 2019, the Interfaith Dialogue forum for Peace established the Pigba Nursery School where nearly 200 students are enrolled. The IDFP supports teachers' salaries and provides learning materials, as well as advocating for official recognition of the school.

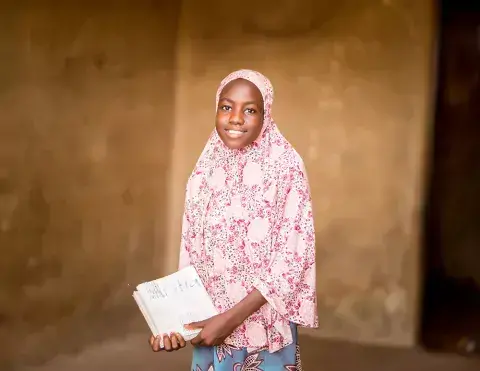

Aisha, 13, a pupil at the school, comes from Borno state. Her memories of the attacks on her community and seeing injured or sick people with no one to care for them influenced her aspirations of becoming a doctor:

“Whenever I saw them (the vulnerable) I felt like carrying them. I will be able to do this with school,” she said.

Aisha does not know why she was never sent to school before, but is glad to be attending now: “I am happy here because I learn and I like mathematics,” she said.

Her classmate Hajara, 12, whose favourite subject is social studies, is excited to be back in school after her education in neighbouring Chad was disrupted due to the insurgency, and then again by the pandemic. Hajara’s eyes welled up with tears when questioned about her experiences in Chad of having to drop out of school and move far away from her mother, who has fallen ill.

Although Hajara is unsure how much or what kind of education her mother, who buys and sells between Nigeria and Chad, attained, she remains Hajara’s source of advice and inspiration.

“She calls me regularly and always encourages me to go to school,” Hajara said.

In March 2021, Nigeria's Ministry of Education announced that 10.1 million children were out of school, up more than three-million from the previous year, which also marked the beginning of the pandemic. Girls account for 60 per cent of this number. Thirty per cent of them were aged between nine and twelve and have never attended school. Experts attribute this rise to the pandemic and lack of security.

Religious leaders such as the members of the IDFP are thought leaders in their communities, and can mobilise action and support due to their positions of relative access and influence. The KAICIID-supported IDFP draws from membership across many religious communities - Christian, Muslim, and traditional religions around Nigeria, utilising their unique access and experience to address social and interreligious issues.

“Pigba camp housing over 2,000 IDPs was neglected and lacking infrastructure,” said Pastor Ibrahim Joshau Adamu, IDFP co-secretary. “During our visit, the children said they wanted to go to school like others. So we mobilised resources and established a school with KAICIID’s help.”

A core mandate for the IDFP is strengthening interfaith relations in the country, foster peaceful coexistence between all religions/ethnic groups and creating opportunity for building trust, confidence and cooperation through dialogue. The platform, according to co-secretary Alhaji Ibrahim Yahaya, contributes to the social economic development of the country by getting directly involved in issues affecting communities such as caring for the internally displaced and supporting interventions such as the Pigba school.

“As an interfaith organisation we cannot divorce ourselves from what is going on in the community and we must have interventions in order to bring succour to the people in the society. Bearing in mind that preaching alone does not solve the problem and that it is until you take practical steps and interests in the affairs of the society, then people will listen to you,” he said.

Being able to attend school transforms the lives of girls like Aisha. Prior to her enrolment, she stayed at home with her siblings where she was vulnerable due to the precarious security situation. “[School] is a cover for me away from the fear I had of Boko Haram killing people in Borno,” she said. “I want to stay here because of school… I don’t want to go back to Borno.” It is no different for Hajara who wants to become a teacher.

Fatima Garba, Hajara’s aunt who cares for her at the camp, was delighted at the school’s opening: “I don’t have an education beyond Islamic school. But I know that education is important because it helps one to progress in life,” she said. “The attacks in Borno were unpredictable and I feared for her safety constantly.”

Salisu, a nine-year-old pupil had never been to school before to coming to Abuja: “I want an education. I like education. I want to become a soldier. I like what they do. I saw them at work on TV,” he said.

“I am happy with the subjects I am taught,” he continued. “Maths and English are my favourite subjects. I also like social studies. I remember a topic we were taught about water being colourless and tasteless,” he said. “I remember this because at home, I have drunk water that is coloured.”

Since the abduction of the Chibok schoolgirls in 2014 in Borno State, the number of attacks on schools have continued to rise with some states shutting them down to ensure the safety of the children. For the children like Aisha, Hajara and Salisu, school not only provides a safe haven from the horrors of conflict, but represents an opportunity and inspiration for a better life.