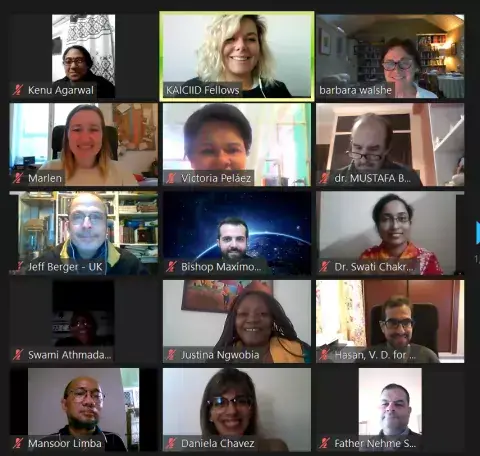

Interreligious and cross-community dialogue must be an enduring feature of post-conflict life, a group of KAICIID Fellows alumni agreed during an online session on Wednesday.

Led by Barbara Walshe, Chair of the Board of Directors of the Glencree Centre for Peace and Reconciliation in Ireland, participants at the online session heard that, to achieve peace in a divided society, opposing voices must be brought under one roof.

“We need to bring people from the edges together, so that at some level people can understand the harm that they are causing each other,” Walshe said. “This way, we can generate an understanding between people who see each other as less than human.”

The Glencree Centre was established at the height of the Irish Troubles — four decades of bitter sectarian and ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland. More than 3,500 people lost their lives in the unrest, which saw Irish Republicans, mostly Catholic, and Ulster Loyalists, mostly Protestant, clash violently in the latter half of the 20th century.

During this tumultuous period, members of the two communities almost never mixed. Walshe, of Catholic heritage, said that, until the age of 30, she had never met an individual outside her religion.

Hoping to bridge the divide amid the bloodshed, Glencree served as a safe, neutral space for both groups to meet. Today, twenty years since hostilities formally ended with the Good Friday Agreement, that work continues, with individuals from all backgrounds coming together to talk, listen, and socialise.

During the session, Walshe discussed with Fellows alumni how lessons and best practices from the work of the Glencree Centre could be transferred to their own specific contexts. Many of the Fellows come from countries that are struggling with civil and ethnic conflict of their own, and during the programme, Fellows are trained to promote dialogue in conflict situations, conflict resolution and peacebuilding.

“Bias and prejudice can often go unexamined, like an underground river running inside every one of us,” Walshe said. “But if you have the dialogue, if you have the listening, if you have the hospitality, it offers the possibility of rehumanising the other,” Walshe said.

Fellows alumni drew on their own peacebuilding experiences, sharing with one another the values that they deem vital to effective reconciliation. ‘Active listening’, ‘tolerance’, ‘respect’, ‘resilience’, ‘patience’, and ‘hope’ came out on top.

Each of these values is crucial to finding common ground — though challenges remain, particularly when animosity is internalised.

“There is a part of human psychology, a primitive and tribal part, that can keep people apart. That is the greatest challenge I have found,” said Swami Athmadas Yami, leader of the multi-religious “Samanwaya Giri” (Hill of Integration). Yami comes from India where violence and hate speech against religious minorities have increased dramatically, in part due to the pandemic, which has exacerbated existing fractures in society and contributed to Othering, stereotyping and stigmatisation of religious and other minorities.

Addressing deep-seated distrust is difficult, participants agreed, but with rigorous interreligious dialogue, it can be overcome.

“One of the strategies we use is getting religious leaders to build friendships in such a way that, when people see that they trust one another, their adherents will begin to trust one another also,” said Justina Ngwobia, a peacebuilding practitioner in Nigeria.

Ngwobia and other Fellows from Nigeria are working to promote interreligious dialogue amidst a Boko Haram insurgency that has killed 36,000 people and displaced over 2 million, and protracted conflict over land rights and resources which has resulted in deep divisions along ethnic and religious lines.

Ngwobia said Walshe’s case study offers many lessons for Nigeria, particularly in terms of restorative justice. Peace efforts in the country have lately focused on reintegrating ex-Boko Haram fighters into society – a task which has faced numerous challenges. “It’s very difficult for the communities to welcome them back.”

Still, she says, the online session has made her hopeful that peacebuilders in Nigeria can change mindsets and hearts. “[In Northern Ireland] they grew up hating one another. Their parents taught them to hate. This is also happening in our own environment. We are trying to teach the young people coming up and also families to learn how to love.”

Though Ngwobia, Yami, and the other participants have completed their one-year Fellowship, the Centre offers continuing resources and engagement — like Wednesday’s session on Northern Ireland.

Providing access to new concepts and perspectives from the field of peacebuilding and conflict resolution is vital, Fellows Programme Manager Kyfork Aghobjian said, as it allows KAICIID alumni to advance intercommunity work in their home countries.

“Education is an endless process. There is always room and space to learn more, get more knowledge, and gain more experience. On top of this, we believe that through these learning opportunities we ensure the sustainability of the programme as we don’t cut our relationships with the Fellows once they have graduated,” he added.

In addition to ongoing exchange and growth opportunities, the Centre offers Fellows alumni a ‘learning and professional development’ grant, allowing successful applicants the chance to further their knowledge through bespoke tuition and cross-party conferences. “We want to provide opportunities for Fellows alumni to grow professionally and continue their journey of interreligious dialogue beyond the work of the Centre. Peaceful societies are built by many hands and many small steps,” said Marlen Rabl, Programme Manager working with Fellows alumni.

As for the online session on the intrareligious conflict on Northern Ireland, the participants were inspired and challenged by Walshe’s take on post-conflict peacebuilding. “The session gave me a new perspective on this important topic,” said Kenu Agarwal, a social, spiritual, and political activist who graduated from the Fellows Programme in 2019. “In India, we need more post-conflict peacebuilding to bring relief to communities affected by conflict, to people who’ve witnessed violence, and their children who hear stories of that violence.”

Agarwal added that the online session reminded her that peacebuilding is a continuous process, which requires dedication and long-term goals. “We have to work patiently and dedicatedly for months, years, and decades at a personal and institutional level to bring about lasting peace.” Bringing the session to a close, Walshe presented the Fellows alumni with a thought exercise, asking each to share ‘what they stand for’.

Appearing on-screen as a word cloud, ‘progress’, ‘tolerance’, ‘sharing’, ‘understanding’, and ‘love’ were the most popular responses. “Against all of that, against all of you, the world of violence has no chance,” said Walshe.