In the wake of a devastating war, the Central African Republic (CAR) has been plunged into a fresh crisis. Its president has won five more years in power but a new coalition of armed groups continues to launch attacks nationwide, inflicting yet more trauma on CAR's civilian population following decades of turmoil.

The country is not only beleaguered by deteriorating security; its media landscape faces severe challenges too. The need for reliable sources of news is critical. Poor journalism can fan the flames of interethnic hostility and provide a platform for hate speech, which in turn paves the way for atrocity crimes.

Yet when reported with ethical integrity and factual rigor, journalism has the potential to empower citizens, enabling them to hold elites to account and make judicious decisions about their own lives and society as a whole. By drawing on transparent and reliable sources that foster trust, news outlets can counter divisive rhetoric and incitements to violence with messages of reconciliation, unity and constructive dialogue.

In short, a good journalist can be a good peacebuilder.

Against this backdrop, the International Dialogue Centre (KAICIID) is supporting an organization in CAR called the Peace Journalist Network to combat hate speech and reduce conflict. The aim is to strengthen the capacity, skillset and conflict-prevention literacy of the network’s journalists as they report on the impact of hostilities and trauma. Today, the network has some 400 members — Central African journalists working in radio, television and print media in the capital, Bangui, and a dozen other towns nationwide.

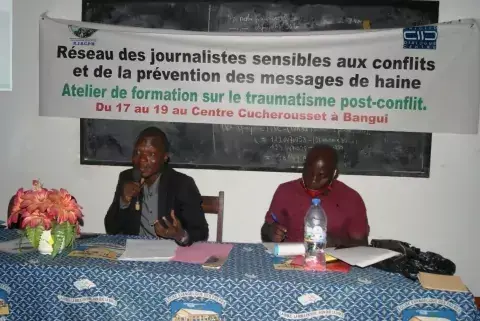

Established in 2018 and known by its French name, Le Reseau de Journalists de Sensibilisation Conflit, the network recently organized a special media ethics workshop in Bangui. The three day training brought together member journalists with medical experts, state officials, university professors and former members of armed groups. Participants developed a code of conduct and ethics and were trained in covering conflict-related trauma— that is, the psychological damage resulting from deeply distressing experiences or violent acts.

“The network is part of a national drive to fight against hateful attitudes and messages, which have become a real danger to the survival of the Central African Republic,” said Boris Yakoubou, KAICIID’s Country Expert in CAR. “The issue of post-conflict trauma has become truly recurrent, given the repeated armed crises that the country has gone through.”

At the end of last year, KAICIID supported a workshop to boost the proficiency of journalists who cover these difficult subjects, clarifying issues around the notion of trauma and explaining how such psychological pain can afflict both individuals and communities, as well as its subsequent impact on wider society.

Participants examined how to sensitively report on rape, which has become a widespread form of conflict-related violence in CAR and is often used to terrorise communities. In 2019, UN Peacekeepers verified 322 incidents of conflict-related sexual violence in the country, although monitoring missions are often hampered by attacks from armed groups and the challenges of identifying victims due to large-scale internal displacement.

Other topics included ways to treat individual trauma, identify post-conflict trauma indicators and tackle this difficult subject as a journalist.

“The training focuses on reporting ethically on conflict without sensationalising or increasing prejudice or stigma,” said Agustin Nuñez-Vicandi, KAICIID’s Country Programme Manager in CAR. “It’s important to report on victims of trauma in a responsible, respectful way that won’t add to the existing trauma that these people have suffered.”

The module on post-conflict trauma indicators was presented by Dr. Caleb Kette, a senior physician in Bangui, who explained how psychological trauma can affect physical health as well as mental wellbeing. Factors influencing the impact of trauma, he explained, include the nature and severity of the incident, its links with previous events, and the support received by the victim.

One former combatant offered his own powerful testimony from the war: “I personally experienced this very violent emotional shock,” he said. “Usually after our operations…I lacked sleep for several weeks. I often had to take drugs to erase the images from my head.”

Further modules explored the importance of identifying trauma during journalistic assignments, as well as highlighting the role that justice can play in relieving the trauma of conflict-related violence.

Participants were also encouraged to brainstorm key proposals for a new code of conduct; its rules stipulate that journalists must verify sources before publication, encourage traumatised individuals to seek professional help, remain impartial towards electoral candidates, and advocate for better mental-health support from the government.

Such principles are acutely needed for CAR’s media outlets, which face external pressures and internal shortcomings. The country is ranked 132 out of 180 in the world press freedom index — worse than other African countries with challenging media climates such as Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe. Its poor standing is due to the authorities’ increasing hostility towards criticism and the danger that journalists face from warring factions — compounded by the impunity enjoyed by perpetrators of such violence.

Newspapers are awash with rumours, smear campaigns and opinionated editorials. They regularly publish incorrect and improperly-sourced information as well as offensive cartoons that can further stigmatise minority groups.

During the pandemic, for example, xenophobic stories in newspapers and on social media have stoked animosity, while other sensationalist coverage continues to create divisions in this already fragmented country. Journalists responsible for inaccurate or unethical reports are not likely to face appropriate sanctions, while serious financial pressures on the media leave some vulnerable to corruption.

“Most of the private press has no state funding or subsidies,” explained Yakoubou. “In addition, journalists are often at the mercy of politicians or other actors who use them for personal, negative ends. The highest bidder, the one who pays well, is always well served.”

Notwithstanding these challenges, there remains a determination among the network's members to overturn the status quo and deliver meaningful public-service information. “Despite the meager annual state subsidy to the media, Central African journalists are making efforts to provide good information from verified and credible sources to the population,” said Michele Mounzatela, the national coordinator for the Peace Journalist Network.

Given the country’s low levels of literacy, broadcasting holds much promise for reaching those unable to read print publications. Enthusiasm for a new era of journalistic endeavor is palpable.

“Radio has a lot of potential in CAR as a vehicle of communication for spreading messages of tolerance and adding to social cohesion,” said Nuñez-Vicandi. “These journalists are excited to be a part of this network. There is a big thirst for good practice and collaboration to ensure this workshop has a widespread effect throughout the country.”