Growing up in a close-knit Jewish Community in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Marcelo Bater’s first experience with religious and ethnic conflict occurred when he was a teenager.

In the 1990s, Buenos Aires was rocked by two terrorist attacks: the 1992 bombing of the Israeli embassy and the 1994 bombing of the Jewish community center (AIMA).

The long history of the Jewish community in Argentina, which dates back to the 16th century, has been marked by both periods of peaceful coexistence and anti-Semitism. Today, Argentina is home to the largest Jewish population in Latin America, with nearly 181,000 Jews centralised primarily in Buenos Aires and the surrounding areas, according to the Jewish Virtual Library. Even so, Jews make up less than 5% of the population in the predominately Christian country.

Deeply affected by the terrorist attacks, Marcelo says he began to see the importance of coalescing around the Jewish identity. “I thought: If we don't care about ourselves, as Jews, as a minority around the world, nobody else will,” he said

While some may have viewed these traumatic events as justification to insulate their religious community from ‘the Other’, for Marcelo, they were the catalyst for a journey towards greater understanding of, and among, religions.

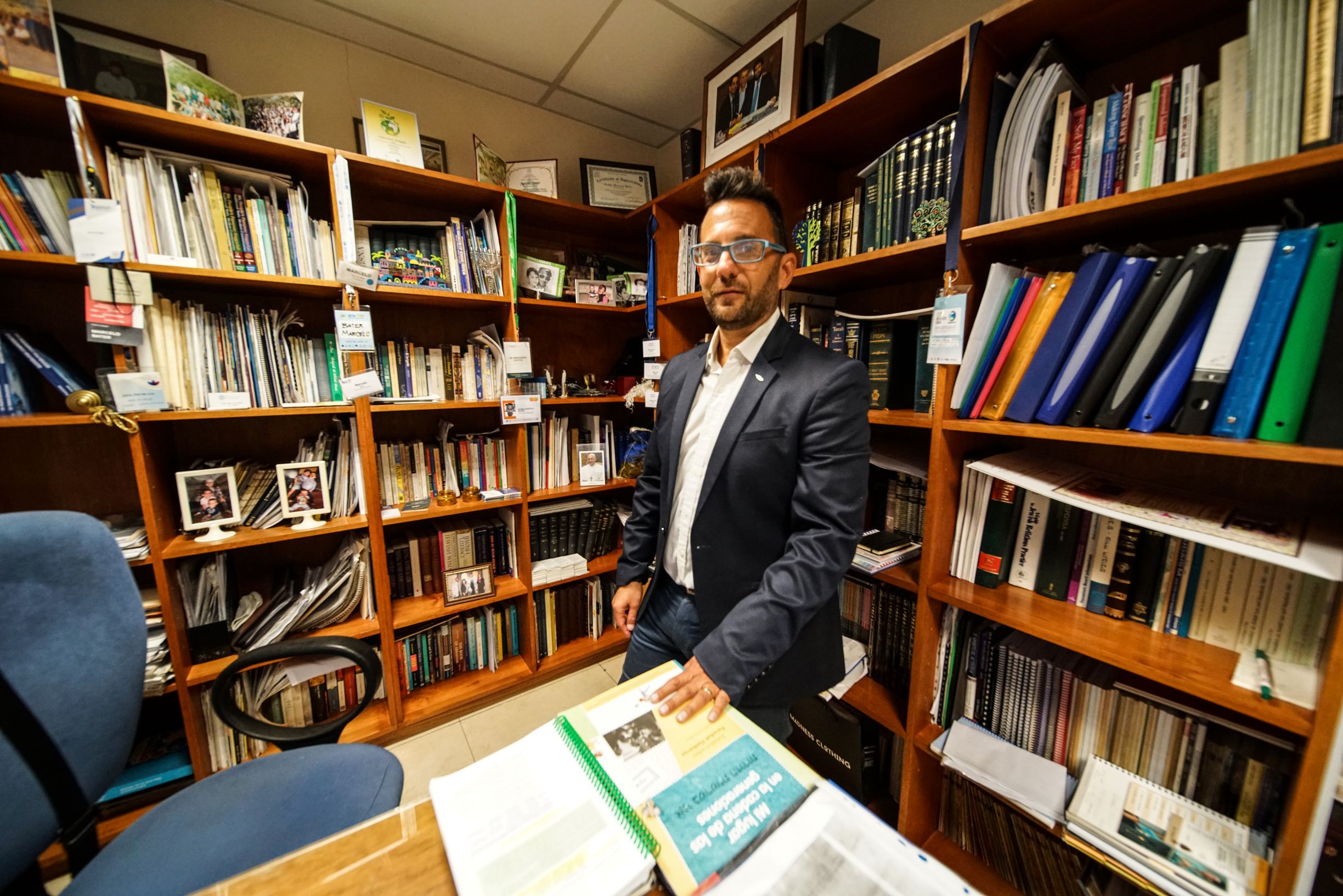

At 26 years old, he became ordained as a Rabbi and following posts in Aruba and Florida, he rejoined the Jewish community in Argentina, bringing with him a clear vision for the country’s pluralistic future. Since then, he has worked hard to ensure representation of the Jewish perspective in local policymaking and to counter anti-Semitism through education.

Marcelo also realised he could make a difference by teaching young children about the importance of interreligious perspectives, alongside imparting the value of Jewish traditions. “I discovered that I really enjoy teaching and that I am in charge of giving Judaism to the next generation. I need to teach why it is important to fight against anti-Semitism and against all intolerance,” he said.

Encouragingly, Marcelo’s vision of a pluralistic Argentina has already begun to be realised. In 2016, the Buenos Aires legislature passed a law which declares the Argentine capital the “City of Interreligious Dialogue”. The law affirms the city’s position as an “environment in which people, communities and institutions from different religious traditions coexist in harmony, value the richness of religious diversity, promote shared common values and build relationships through dialogue, reflection and cooperative actions in order to strengthen the social fabric for the common good.”

This effort was largely supported and promoted by the Latin American Jewish Congress (CJL), an organization founded to keep the Jewish tradition alive and keep dialogue with other faiths, where Marcelo is a member. It is also through the CJL where Marcelo learned about the KAICIID Fellowship Programme. He joined the international cohort in 2018.

Interacting with a diverse group of people from countries around the world, Marcelo found his passion for pluralism and interreligious dialogue to be fully affirmed. “Everything I learned as a Fellow has helped to reinforce my belief that dialogue is really the only route to peace. Since becoming a Fellow, it has reinforced for me that we need to talk to everyone, at every age, about how religion is misunderstood,” he said.

Marcelo said this has struck home for him, particularly in regard to anti-Semitism. “When you see someone drawing a swastika and you talk to them, and ask: ‘Why are you doing this? Do you know what it means?’ Most of the time, you realise that these people have no idea.”

As much as being able to talk to members of the local community matters, Rabbi Marcelo says that learning dialogue practices from KAICIID taught him something much more valuable: the importance of listening. “Each time the Fellows came together in person, the focus was on dialogue; on listening to what ‘the Other’ wants to say. Because when you talk about dialogue, when you talk about a different point of view and you're a good active listener, you realise that things that you thought were confronting, are not so confronting,” he said.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, this revelation became crucial to how he performs his duties, as pastoral counselling moved from the physical to the virtual world. “I now use the phone 24 hours a day because people need to be in contact. We are isolated with our families. And if you don't have any family, you are completely alone,” he said.

Marcelo says the ability to listen is “the most important tool for 2020”, because it equips individuals with the tools to break down stereotypes, enhance inclusion efforts and amplify the voices of the underrepresented. According to Marcelo, this is just as true for Jews in a majority Christian country, as it is for people who are isolated and anxious during a global health crisis.

He has also joined Argentina’s Faith Phone Chain (Cadena Telefónica in Spanish), a multireligious initiative established by the government, which connects anxious or isolated individuals with a leader of their faith. Marcelo sees the phone chain as yet another way to practice his life philosophy: that it is important to exchange different life experiences, understand the stories of others and be good listeners.

“We may have different religions, but It doesn't matter if God is mentioned in this name, in another name, in another name”, he said. At interreligious meetings, I used to refer to God as The God of Many Names. This God, by whatever name, wants us to create a peaceful world.”