At the height of Myanmar’s Saffron Revolution in 2007, Harry Myo Lin joined thousands of Buddhist monks and frustrated citizens in the streets of Mandalay demanding political and economic change. It was the then-16-year-old’s first foray into interreligious activism after a childhood steeped in interfaith dialogue.

“My father was a conservative Muslim, my mother a liberal Muslim, I studied English at a Catholic nunnery, and one of my best friends was Buddhist,” he said. “I grew up in a diverse quarter of Mandalay with harmony among the faiths.”

That harmony began to fray in the years that followed as predominantly Buddhist Myanmar emerged from decades of military rule. New freedoms brought new challenges. Once isolated, the country was suddenly online, and rampant flows of misinformation were contributing to sharp spikes in interreligious and interethnic tensions.

In 2012, fake news and hate speech circulating on Facebook stoked violence between Buddhists and Muslims in western Rakhine State, leaving thousands displaced and hundreds dead. Harry reached out to the monks he had once protested with to brainstorm solutions and ended up living in their monastery for two months as they formulated a plan.

“We agreed we must work together to prevent violence,” Harry said. “These monks were a living example for me. They treated me with such kindness and inspired me to forge ahead with interfaith engagements.”

In 2013, Harry started a secret Facebook group to combat the online spread of dangerous fake news in Myanmar. Group members fact-checked false rumours and distributed accurate information to religious and community leaders to set the record straight and ease tensions.

The need for this group was tragically reinforced that year when clashes killed more than 40 people in Meiktila. These events so close to Mandalay inspired Harry to launch The Seagull: Human Rights, Peace & Development, a group of interfaith leaders and activists who collaborate to promote dialogue and protect religious freedom. The Seagull worked in Meiktila to document violations that had occurred during the anti-Muslim riots and to encourage strained communities to reconcile. Harry attracted praise for this work but also harassment and threats.

“During one Seagull training for Buddhist monks and nuns, several ultranationalists accused me of trying to convert Buddhists to Islam. They harassed me and forced me to stop the training, so I had to go into hiding for a week,” Harry remembered.

Photos of Harry with Buddhist friends were posted with comments such as, “Muslims like him should be killed.”

Harry says the loudest and most harmful hate speech in Myanmar often targets Muslims, other religious and ethnic minorities, women, and LGBT people.

Harry joined the Panzagar (“flower speech”) movement in 2014 to counter hate speech against these and other persecuted groups in the country. Participants placed flowers in their mouths to symbolise their commitment to spreading “right speech” and opposing dangerous falsehoods spread person-to-person and via large-scale public media campaigns.

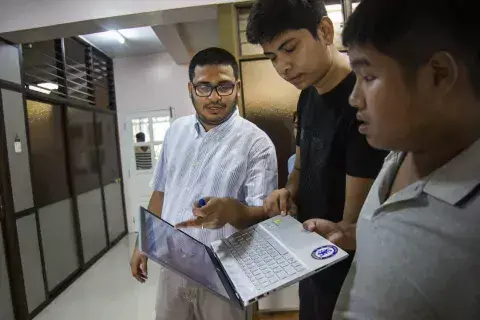

After coordinating Freedom House’s religious freedom programme and teaching conflict transformation at the Institute for Political and Civic Engagement for several years, Harry now serves as KAICIID’s country expert in Yangon. In this role he supports the Paungsie Metta Initiatives (PMI), a multireligious network of Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, and Muslim faith leaders and civil society organizations who promote harmony through interreligious trainings, interfaith forums, inclusive dialogue events, and peace celebrations.

“Before KAICIID, local policymakers were not hearing the voices of religious leaders. Now that we’re building national networks and bringing these groups together to strategise, we can work to achieve long-term structural change,” he said.

The PMI has already hosted more than 3,000 religious leaders and civil society representatives for training workshops aimed at mitigating conflict and promoting social cohesion. Harry is now setting up an interreligious dialogue centre that will host intensive conflict transformation courses for youth and faith leaders, teaching them how to use social media to combat online hate speech.

“Empowering religious leaders to use social media in positive ways creates new space for dialogue,” he said. “By promoting the basic tenets of their religions, they can challenge the misuse of faith as a means of violence and promote the idea of a united Myanmar that is equal and welcoming for everyone,” Harry said.

The PMI’s Facebook page spreads positive messages to thousands of followers as Harry’s secret Facebook group still works behind the scenes to stop violence before it starts.

“When a Muslim man was accused of raping a Buddhist woman in northern Shan State recently, our group reached out to local leaders in the region to address calls for violence against Muslims and to make sure local authorities arrested the man. This helped prevent the situation from escalating,” he said.

Fake news and online discrimination towards minorities remain key challenges in Myanmar. With Harry’s guidance, local religious leaders are working harder than ever to quash misinformation and stop violence. He hopes the PMI will encourage government officials and policymakers to do the same and is fighting with renewed vigour, now for his infant daughter.

“Whenever I think about the discrimination religious minorities face in Myanmar I worry for her generation,” Harry said. “We need to heal from the trauma of living under military rule, but we also need to solve these issues in our lifetime so that our children can lead better lives.”