Arno Michaelis and Pardeep Singh Kaleka met under horrific circumstances.

In August 2012, a gunman murdered Pardeep’s father and five other worshippers during Sunday morning services at the Sikh Temple of Wisconsin near Milwaukee. The shooter, who killed himself after the attack, belonged to a white supremacist group Arno helped form in the late 1980s.

Arno and Pardeep became unlikely friends and collaborators in the months that followed, an incredible story of resilience and transformative forgiveness.

The two men were born on opposite sides of the world. Though they both grew up in Greater Milwaukee, their early lives ran perpendicular. Arno was raised in a nice neighbourhood, but his childhood was far from perfect. Hurt by family troubles, he began lashing out.

“I went from bullying kids on the bus to starting fights at school to beating people up. By 16 I was a full-blown alcoholic. White power skinhead music introduced me to the ideology of hate, and some friends and I started our own hate-metal band, which helped grow our gang the Hammerskins into the largest white supremacist skinhead group on Earth.”

Several kilometres away, Pardeep and his younger brother were just trying to fit in. His family had left their farm in India when Pardeep was six and moved to Wisconsin in search of a better life. He remembers the transition as a steep learning curve and a constant struggle for stability.

“We went through a lot of assimilation,” Pardeep said. “I remember my father cutting our hair, an important religious symbol for Sikhs, after kids teased us about how long it was. It hurt him to have to do this because he saw it as losing part of our identity and spirituality.”

As Pardeep perfected his American accent and baseball swings, Arno increasingly isolated himself from mainstream society. He dropped out of school at 16, wrote songs about exterminating racial, religious, and sexual minorities, and wore swastikas to work.

“The owner of the T-shirt company where I worked was Jewish. He not only let me keep my job but hired my skinhead buddies too. It was hard to maintain our anti-Semitic tropes when the only Jewish person we saw regularly treated us so kindly,” Arno said.

Similar kindness from black, Latinx, and gay colleagues started chipping away at Arno’s hate.

“The big factor that led me to leave the gang was exhaustion,” he said. “I knew it was wrong to hate and attack people because of the colour of their skin and I was constantly expending energy to deny that. These people I claimed to hate treated me with compassion I didn’t deserve. Nothing drove home the wrongness of my actions more than that.”

In 1994 his daughter was born and a second Hammerskins friend was murdered. He left the gang and never looked back.

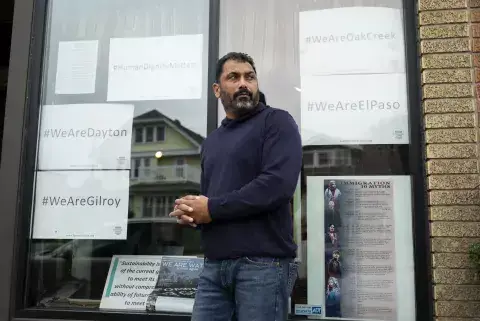

Arno later wrote a memoir and started an online magazine called Life After Hate that featured articles about compassion from contributors all over the world. That’s where he was when Pardeep reached out after the Sikh Temple shooting in 2012. Strangers at the time, the two men met for dinner.

“I was trying to understand the shooter’s motivations,” Pardeep said of his decision to contact Arno. “We came to the conclusion that hurt people hurt people, and that pain that is not transformed is transferred. More important than the shooter’s motivations was our response. If hate begets more hate, the cycle of misery continues and often escalates, so we needed to figure out how to respond to prevent another shooting.”

“In that first meeting, Pardeep and I spoke for four hours and realised we had so much in common despite our different backgrounds,” Arno remembered. “My vision for Life After Hate was about bridging cultures and bringing people together. By the time we finished dinner, we knew we would be working together.”

Pardeep and others who lost loved ones at the Sikh Temple had been brainstorming ways to reduce hate-based violence. When Pardeep invited Arno to speak with him at a local high school, Serve 2 Unite was born.

“Individually our stories are strong, but together they transcend the atrocity that happened and deliver a message that the human spirit is resilient, and that forgiveness is the ultimate form of power,” Pardeep said.

Serve 2 Unite uses dialogue, solutions-based problem solving, service learning, and artistic expression to help young people establish a healthy sense of identity, purpose, and belonging. Their school programmes address gun violence, racism, sexism, homophobia, and religious intolerance, helping divert youth from violent extremist ideologies, bullying, substance abuse, and other forms of harm.

Since that first high school assembly in 2013, Serve 2 Unite has reached more than 10,000 students at more than 40 schools in Southeast Wisconsin and engaged with thousands of other young people across the U.S.

Akaya sticks out in Arno’s mind as one student Serve 2 Unite’s work helped transform.

“She was the holy terror of her school, but after hearing our stories, Akaya went to her teacher and said, ‘I won’t start fights anymore. I’ll stop them from happening by getting people to talk’,” Arno recalled.

She followed through on that promise, organising weekly summer block parties for children in Milwaukee’s heavily segregated inner city and eventually getting an internship at a local organisation that works to build safe and empowered neighbourhoods.

In 2018, Arno and Pardeep co-authored a book called The Gift of Our Wounds documenting their journey together and current work with Serve 2 Unite.

“We think we can escape our past because time has passed, but sometimes time does not heal wounds, it makes them worse,” Pardeep said of the title. “Arno promised me the day we met he would do what he could to cleanse the wounds of our past. The book explores how we atone so that we can heal properly moving forward.”

A shooter’s fear, ignorance, and hatred brought Arno and Pardeep together for the first time in 2012. What binds them now is a shared commitment to transform these evils into courage, wisdom, and love.

Arno and Pardeep are featured KAICIID Heroes of Dialogue. To find out more, click here